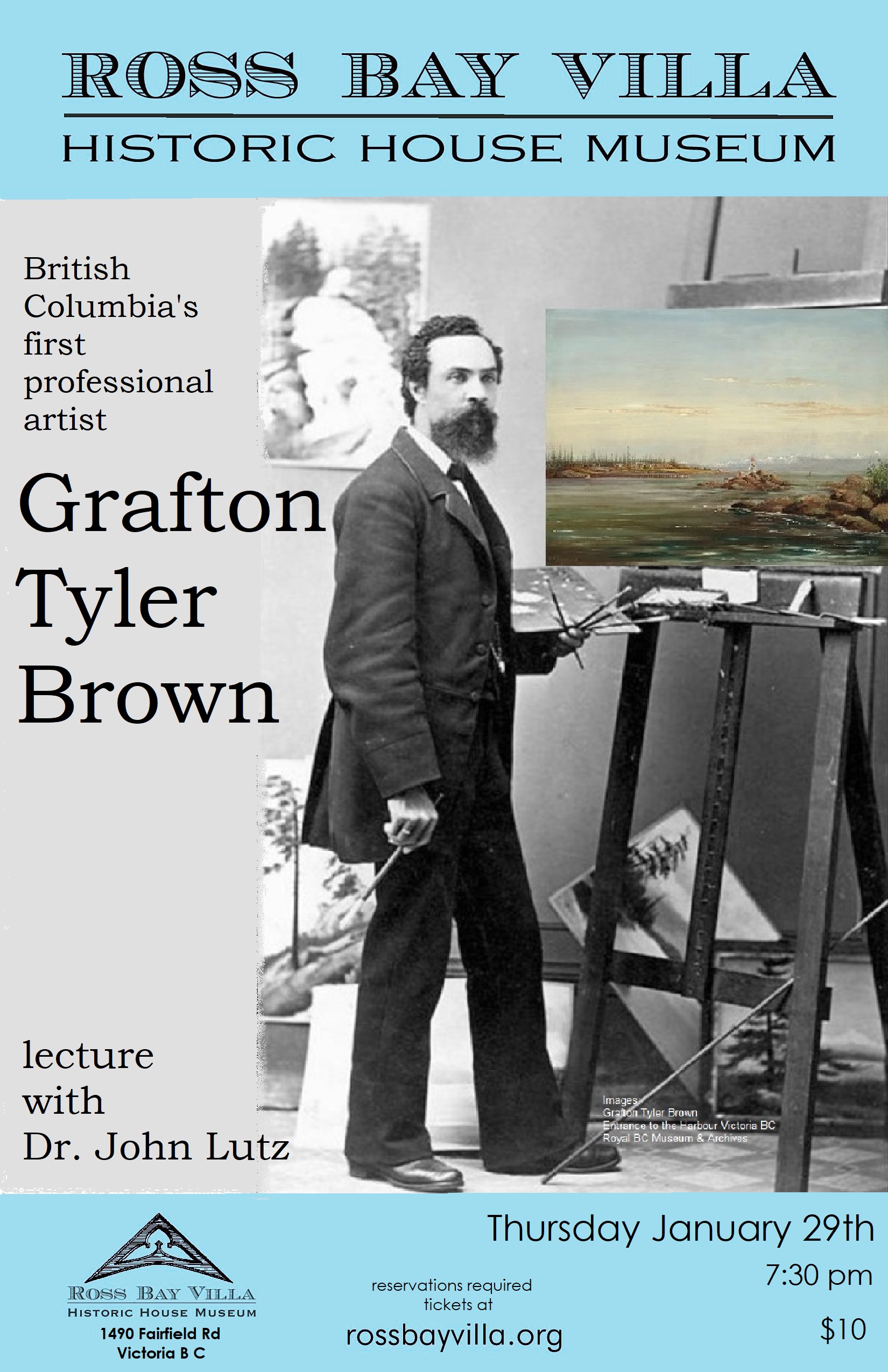

Join us at Ross Bay Villa Historic House Museum on January 29th at 7:30pm for our first lecture of 2026. Professor John Lutz will speak about Grafton Tyler Brown’s time in British Columbia as the province’s first professional artist.

Grafton Tyler Brown was the most famous African American artist of the American West, but he is almost unknown in British Columbia where he started his professional career and where he was considered “White”. Born to a free Black couple in 1841, he established himself as a printer and lithographer in San Francisco. When he wanted to reinvent himself as a professional artist he joined a survey party of southern BC as a draughtsman, sketching the impressive scenery around him and offering a window into the life of BC in the 1880s. He set up an art studio in downtown Victoria, and presented an impressive show of paintings developed from these sketches, and was declared BC’s first professional artist!

Dr John Lutz is the former head of the University of Victoria’s History Department. He is a popular presenter at Ross Bay Villa, the author of numerous books and articles exploring the past of Western Canada, and an expert researcher and speaker. He will explain the process of unearthing information and images related to the life of this famous but not well documented historical figure, as a lead in to Black History Month. Tickets are $10 and must be reserved in advance at https://tinyurl.com/56f4use7. All proceeds support the Ross Bay Villa Society, the volunteer based organization that runs and owns this 1865 heritage site.